This is a big year for June in Buffalo, marking both the 40th anniversary of the festival's founding and the 30th anniversary of David Felder's tenure as artistic director. Under Felder's direction, the festival changed significantly, placing a greater emphasis on student works, and bringing in a wide range of skilled composers, performers, and ensembles.

|

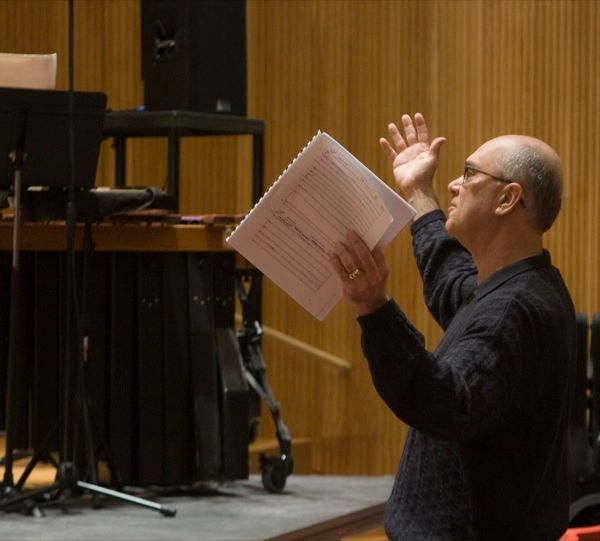

| David Felder |

Felder, who serves as the Birge-Cary Chair in Composition at UB, has long been recognized as a leader among his generation of composers. This year, JiB will see the performance of several of the composer's key works, including his brass quintet, Canzone XXXI (to be played by the Meridian Arts Ensemble), his set of orchestral variations, Six Poems from Neruda's "Alturas…" (to be played by the Buffalo Philharmonic), and his recent Les Quatre Temps Cardinaux, which will be performed by SIGNAL with members of the Slee Sinfonietta (see our post from its October performance). The latter work, a fifty-minute song cycle for two voices, chamber orchestra, and 12 channels of electronics, sets poems by René Daumal, Robert Creeley, and Dana Gioia. All three works, like most of Felder's output, are characterized by their energy, lyricism, and what Dansk Musiktidsskrift has called "an impressive ability to establish a sound universe, in which one is taken through every corner of experience."

I recently had a chance to interview Felder about the festival, and some of his recent work.

When you restarted the festival in 1986, what were some things you set out to do differently from the way it was run in the past?

It was a very big philosophical change, which was based on the way I assessed the field as a young composer myself at that time.

When I was in California, I was like a lot of other younger composers. I didn't really feel that I'd had a good performance of my work until I was about 28 years old. It was mostly student performers or conservatory faculty members who didn't care at all about playing a younger composer's work. Though I could understand why people didn't want to spend the time on a young composer's work, I thought it was really difficult for me and every other young composer I knew to evaluate what we were trying to do. I took a look around, and I saw that there were only a few other opportunities for young composers to have strong performances of their work. Those were places like Aspen, Tanglewood, Davidovsky's summer program at Wellesley, and the summer program at Yale (the latter of which I was fortunate enough to attend). But those programs were extremely selective and almost entirely Ivy League, so the majority of younger composers around the country were kind of stuck, particularly the composers on the West Coast.

|

| Felder with student composers at JiB 2010 |

By the time I moved to Buffalo, the June in Buffalo festival had been dormant for a long time. So I proposed that I bring my vision and restart the festival, but under the terms I'm outlining here. I considered Feldman a friend and had great respect for him, but we had differing views on what it meant to be a young composer. He did not believe that young composers deserved to be presented in the way that I was presenting them. He thought that they should sit at the feet of the geniuses and catch any pearl that might fall from their lips. So the old June in Buffalo program did not feature performances of young composers' music, they just sat in seminars, and the concerts were portrait concerts of individual faculty composers. It's a very different philosophy about how one teaches and how one helps young composers develop.

What were some of the difficulties restarting a festival which had been dormant for several years?

When I arrived, despite promises to the contrary when I interviewed, there was absolutely no money. So I had to do everything with zero budget, and I had to raise the funds completely those first years. I was able to find some interesting solutions, and the budgets started to stabilize after the third or fourth year, particularly when I became the Birge-Cary Chairholder and could dedicate resources. I am proud that even from the beginning there was never one year in which there was a deficit.

Also, the first year we had to work hard to get applicants, I had to call around a lot. Very soon, though, we began to attract a large pool of applicants, allowing us to be very selective about who we decided to invite. And the festival fairly quickly became an obvious success. And now, there's not a week that goes by where I don't see another new festival imitating JiB. There are loads of them out there now—even some of our former student assistants for JiB are copying us. It causes me to think about what the field might need next, since such events have proliferated now to the point of near-absurdity.

Also, the first year we had to work hard to get applicants, I had to call around a lot. Very soon, though, we began to attract a large pool of applicants, allowing us to be very selective about who we decided to invite. And the festival fairly quickly became an obvious success. And now, there's not a week that goes by where I don't see another new festival imitating JiB. There are loads of them out there now—even some of our former student assistants for JiB are copying us. It causes me to think about what the field might need next, since such events have proliferated now to the point of near-absurdity.

Are there any JiB performances that you have found particularly memorable?

There was a New York New Music Ensemble performance of an amazing work by Jacob Druckman called Come Round, which is really one of his great pieces. I just remember that the performance [at JiB 2000, conducted by Harvey Sollberger] was absolutely hair-raising! And a few years ago [2013], Charles Wuorinen conducted the Slee Sinfonietta in a performance of his chamber cantata, It Happens Like This. That was a really great performance. Having the composer here conducting the group was really very special.

But there are so many of them, it's really difficult. So I'm singling out just a couple which were absolutely breath-taking.

The Performance Institute is doing the Druckman this year on their June 5 concert at Kleinhans.

Right, and that's being programmed because we really wanted to get that piece on the festival. Jake Druckman was a big part of the early years of JiB, he came quite a bit and he was extremely supportive of me and also supportive of the festival.

It seems that there's always been a lot of variety amongst the faculty composers who have been here over the years.

One of the hallmarks of the way that I program the week is that I don't bring in people to be on the faculty with all the same viewpoints—in fact, I actually deliberately select people so that there will be some friction between ideas, so that students might get input that's 180º opposite from one master class to the next. I mostly enjoy very diverse groups of composers working together because you can learn the most that way if you have a strong individual internal motivator and your own vision to follow. If you're looking for consensus, JiB is not necessarily the place for you.

Were there any JiB performances of your own works that are especially significant to you?

|

| Felder coaches performers during a rehearsal of Tweener |

Otherwise, any time that I hear my string quartets played is great. For example, a few years ago [2013], JACK astonished me by playing the living hell out of my second quartet, Stuck-stücke, and that was really gratifying. Of course, the Ardittis play it extremely well, but to then have a next generation quartet pick it up for the first time and play it absolutely brilliantly, that was wonderful!

One of the new things the festival has been doing in recent years is the Performance Institute.

There have been a lot of initiatives over the years, I've tried to do a lot of different kinds of things. Years ago we had an emerging ensembles program, so groups that were just coming out of conservatory or had just formed in New York were invited to come and be resident ensembles at the festival. For example, Brad Lubman had a group when he was at Stony Brook called the New Millenium Ensemble, which had just formed, so I invited them to come. The Meridian Arts Ensemble was another one of the original groups that came under those programs, and there were lots of others. We also tried a couple computer music initiatives. And then we did some thematic programming for a number of years, where we looked at specific interactions between, for example, "Music and Text," and so forth.

The Performance Institute is another initiative, it's something that we're piloting right now to see how it might work, and it could be a nice broadening of the festival.

Is there anything in particular you're looking forward to about this year's festival?

|

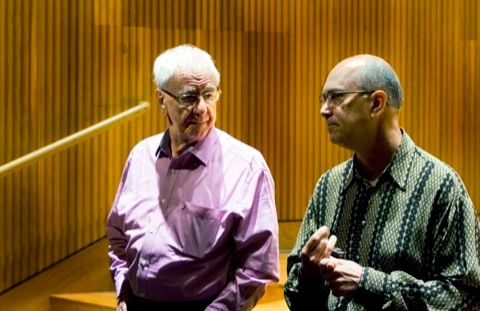

| Felder and Bernard Rands at JiB 2014 |

What would you say is the most significant development in your music since the mid-1980s when you restarted the festival?

I see it all as one very connected line, so I don't think that there have been any giant changes. I would say that the work has perhaps become less technically demanding in terms of what is asked of the players, and more demanding in terms of their ability to contribute just the right sound. In some of the earlier work there's a lot of complexity on the page, which may not have yielded the same level of complexity in the sounding result (this is typical for younger composers). So I'm happy now to allow the complexity to exist in the sounding event, and I take a lot of joy in getting out of the way more than I used to.

It seems like there's an increasingly present "spiritual" component—for lack of a better word—at work in your music (I think of Shamayim, Requiescat, and Les Quatre Temps Cardinaux), which seems to contrast with older pieces like Linebacker Music or Canzone XXXI.

It is there, and it's strongly there underneath. Even if you look at the earlier pieces, the sources may appear less overtly "spiritual," but what's underneath the brass quintet, for example, is Dante. What's behind that piece is an unfinished canzona from La Vita Nuova. So it may be a little more on the sleeve now, but it's always been there.

That's interesting, because it seems like a lot of your works make direct reference to, or take inspiration from, poetic texts (e.g., Six Poems from Neruda's “Alturas...”, Les Quatre Temps Cardinaux).

I think the reason goes back to when I was coming of age as a composer. The older fixed forms held no appeal for me at all. I was not interested in writing multi-movement abstract suites, nor was I interested in following any of the existing fixed forms, instead I was looking to try and create my own formal vehicles and containers.

There are many ways to create those containers. For example, if you go back and read Simple Composition, Wuorinen argues very convincingly that one can extrapolate from aspects of the time point and build the form purely from concrete musical abstraction. But for me, I wanted to find something that could be an inspirational touchstone, either that I could constantly refer back to as a way of looking to see if I was actually doing what I thought I was, but more importantly, to give me the opportunity to create forms which were modeled on some kind of psychological or spiritual profile that could be extracted from texts—not so much literally, but more as a way of modeling a behavior.

So, for example, the piece BoxMan refers to the novel by Kōbō Abe. I was reading that at the same time I was reading Konrad Lorenz's book, On Aggression. In that book, Lorenz is looking at the long relationships of Greylag geese: they pair up, male and female, and stay together for virtually their entire lives. And yet, they manifest these varying kinds of aggressive behavior, which he studied as a way of looking at aggressive behavior in people. Somehow, that was assembled in my mind with the lead character called the "BoxMan" in Abe's novel, and the result was a form which was a pure musical abstraction—one that works like a long set of variations. The controlling forces in the variations are some behaviors that I abstracted from those two books. So that's why you see some performance directions in the score like, "threatening," or "manic."

Your recent piece, Les Quatre Temps Cardinaux ["The Four Cardinal Hours"], is a much more large-scale form, which is based on the cycle of a single day. It occurs to me that a lot of large-scale works seem to take these seemingly mundane cycles as stepping-stones to larger forms (e.g., the days of the week in Stockhausen's Licht, or Joyce's Ulysses, which is also based on a single day). Were any of those earlier works reference points for you?

Not directly, but when I interviewed Stockhausen, he said something that was very powerful for me. I had asked him about circular forms, and he said, "No, it's a spiral." I hadn't ever considered that before, and that simple sentence changed a lot for me in my own thinking about form.

The idea is that these are ways that we measure temporal existence. So that's why larger works have a tendency to use these as models in some way. The very short Daumal poem, which is at the heart of LQTC—something he did very late in his life when he was close to death, after not writing poetry for years—was extremely powerful to me for its simplicity and clarity. When he was a young man, he wrote extremely complicated automatic writing pieces, but through the course of his own creative life, and his contact with Hindu art-forms, he came back to something that was extremely simple but very powerful and direct, in that it works on an inner level with its imagery.

The other poems, by Robert Creeley, Dana Gioia, and the reference to Pablo Neruda, are much more personal articulations of that larger transpersonal kind. One of the great things about Creeley is that he can take a very simple moment that occurs in a day, and connect it, in a very subtle way, to much larger senses of time. For example, there is one poem of his [“Kitchen” from Thirty Things, 1975] in which he's in a room, watching the light change as it comes through some lace curtains, but he's watching the light change indirectly on the floor, and that's a reference point. It's very subtly done, he doesn't draw attention to it, but through that illustration the individual poet is connecting the passing of his own life to the larger life of man. So that was the idea of the formal wheel in LQTC.

|

| Brad Lubman conducts Felder's Les Quatre Temps Cardinaux |

I'd say I'm attracted to the unexplored regions, it's like Amundsen going to the South Pole or people who go down into the depths of the ocean in bathyspheres. I know there's a power in the low register that is very profound. Much of contemporary music has been very focused on the attack point, but I'm interested in the movement of voices in the lower register which are not solely based on attack point or harmonic movement but are instead coloristic or resonance-reinforcing movements. I'm also interested in the very highest registers.

There used to be three body types people talked about: ectomorph, mesomorph, and endomorph. I used to joke that I was mesomorphic (which is a body type that is wider at the hips), and so much of my music revolved around middle C and the octave below. I think it's because of the tessitura of my voice: I was a tenor-baritone and was a singer my whole life, so naturally, somehow, that's where my pieces originated. And I noticed years later that many of my pieces work out from that register.

Even LQTC begins its unfolding from the F# in that octave.

Yes, it's meant to start there, due to the importance of B (the piece is very A/B centric). The F# is also important because it's the 11th partial of a C fundamental. And if you look at the piece, you'll see that there are certain pedal tones in the beginning, which essentially set out the work's major harmonic focal points.

I’m definitely looking forward to hearing that again at the festival this year. Finally, when it comes to June in Buffalo, its legacy, and its longevity, what are you proudest of?

I don't know that I think in those terms. If I had to answer that, I'd say that we've probably done performances of around 700 or more young composers' pieces, and those performances and the help that we've given to people over the years, I think has been really important to the profession.

I'm extremely grateful to the University at Buffalo, and Buffalo arts organizations, as well as our donors, university patrons, audiences, and composers—both student participants and faculty members—who have participated and supported this endeavor over the years. Without that support, we certainly would never have gotten off the ground. So it's very gratifying to continue to feel that Buffalo is a place that supports work that is innovative and hopes to advance the conversation about the ongoing developments in the field, whatever they may be.

June in Buffalo has certainly been a locus for the musical conversation to continue, with energetic and adventurous performers willing to dive into the uncharted territories being carved out by today's composers. And the festival will surely continue for years to come, with hundreds more young composers hearing great performances of their work, further encouraging these emerging artists to keep surveying unexplored sonic regions.

—Ethan Hayden